Tales From Birehra - Epilogue

Search For Utopia

The memory of Birehra has flashed through Azad’s mind at odd times and in odd places. He has remembered his little village while strolling along the Champs-Elysées, while grasping the iron gates of Buckingham Palace and looking down at Rome from the top of St. Peter’s Basilica. He often thinks about the story of a mountain, which his grandmother told him when he was a little boy. “As you walk away from the mountain, a voice calls you from behind. You can hear your name clearly, but if you dare to look back at the mountain, you will be turned into stone instantly,” Grandma had said.

Birehra is that mountain for Azad. It has called to him all these decades, but he has never dared gather enough courage to turn his head.

Sometimes he feels as if he left Birehra just yesterday, even though it was over seventy years ago when he was only six years old. It feels as if he has travelled halfway through the globe - the only way to return to Birehra is to dig a hole in the ground, pass through the centre of the earth, and emerge on the other side. It is only 400 miles away, but each mile is a light-year long.

“Don’t ever look back, son,” his father had told him as they had crossed the border.

Azad prefers fantasy over reality because fantasy allows him to live without all those obstacles and irritants that come with reality. There was a time when he lived in reality and was often disappointed when his characters did not behave the way he wanted them to. So he chose fantasy as a way of life and calls it smooth sailing, devoid of annoying crests and ebbs.

He often fantasizes about sitting in a movie theatre centre, watching his life on the big screen. From time to time, he looks through the darkness at the empty seats around him and then turns his gaze back to the screen. As his life follows the screenplay, he wonders how much control he has had over the script. He asks himself if he really needs to have any control, but then he edits the script as he goes along, adding a tear here and a smile there. While he watches events unfold, he reminds himself that he is merely an actor following a script. All thrills, joys, pains, and agonies that he has gone through in life are part of that script; he disowns them in favour of the actor on the screen. This way, he can eliminate the perilous rapids, as he rafts through the serene flow of time and manages to camouflage his pain under the smile of Buddha.

Azad does not believe in borders. If the earth were supposed to be divided into countries, it would have natural walls and partitions separating nations and tribes. When he globetroted through many countries in his backpacking days, he found that all babies cry and giggle in the same language, regardless of their nationality. He discovered that all hearts ache at the loss of their loved ones, and all lovers feel the same ecstasy when they meet, regardless of their race.

As we grow older, we gain wisdom at the expense of agility. Slowly and slowly, we settle down into the age of reflection. Azad knows that the downtown streets are still bustling with crowds of young people on Saturday nights. Movie houses and restaurants are still packed. The City Hall's rink is still crammed with skaters gliding majestically with their hands in their pockets. There are still lineups of excited fans at the box office to get tickets to Toronto Blue Jays games, and crowds still now go wild at every home run. But Azad has had his share of excitement. Now he prefers to spend his evenings sitting in his rocking chair, watching episodes of I Love Lucy from the old days.

After planning for forty years, he finally took a trip to his old alma mater. It was like a pilgrimage for him. He visited old labs and classrooms from forty years before. He sat on a bench in front of the old cafeteria, where he used to sit with his friends and engage in hot discussions about Vietnam, hippies, and Mao Tse-tung. He looked around and noticed that the grass on the campus was not as green as it used to be in his day, and the co-eds not as beautiful. Deep down, though, he knew that the grass was even greener, and the girls even more attractive. He simply did not have the same eyes anymore.

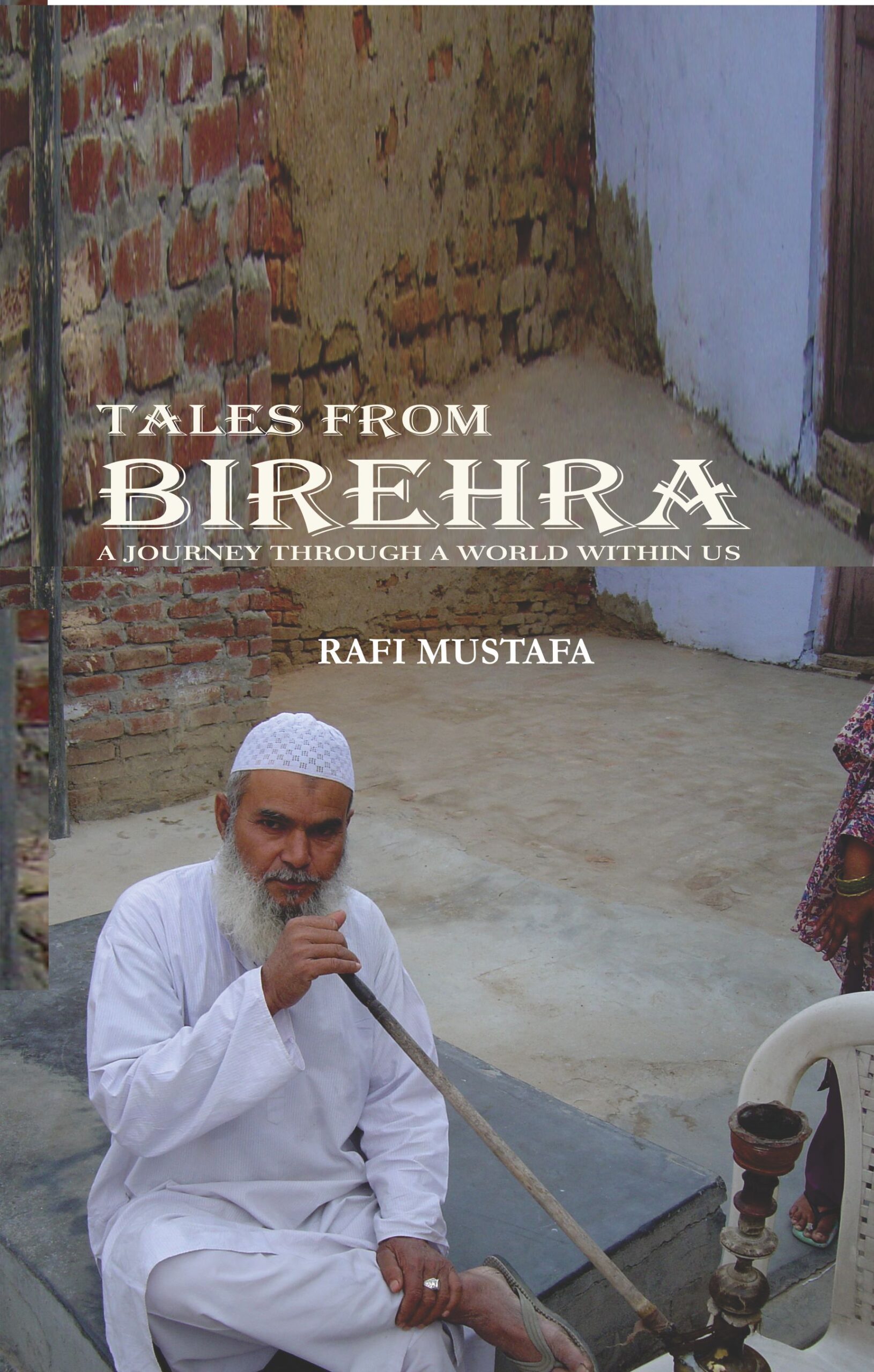

At one time, Azad used to search for a utopia. He looked from Sparta to Moorish Spain, from the Ottoman Empire to the Soviet Union, and from Maoist China to capitalist America. He followed every ism, ocracy and archy, but always returned empty-handed. Finally, he gave up his pursuit and decided to create his own utopia. He calls it Birehra. The life in Birehra is simple. There are simple problems with simple solutions, and it does not take much to be happy. It is not like these countless other places, where we need big things to make us happy, and every little problem looks like a mountain.

Azad believes that Birehra still exists, just as he had left it seven decades ago. He is six years old once again and can clearly hear the dull sound of the bells hanging around the necks of oxen, which are on their way at dawn to plough the fields. He still runs with his friends after dust devils, throwing pieces of paper into them to see whose paper will go highest. He still hears the shrill call of a cuckoo bird perched in a mango tree. As a sudden gust of wind passes through the fluttering leaves, the bird flies away, and the spell is broken.

Azad’s friends are convinced that he is at the crossroads of nostalgia and schizophrenia. He erects every mud wall in Birehra with his own hands, puts the characters of his choice in every house, and engineers every event with utmost care. He disagrees with his friends when they tell him that Birehra is just a mirage that he has been chasing all his life. He does not believe in mirages since he knows that every oasis, appearing on the far side of the quivering desert heat, is real. All a weary traveller needs, is the unwavering passion to reach it.